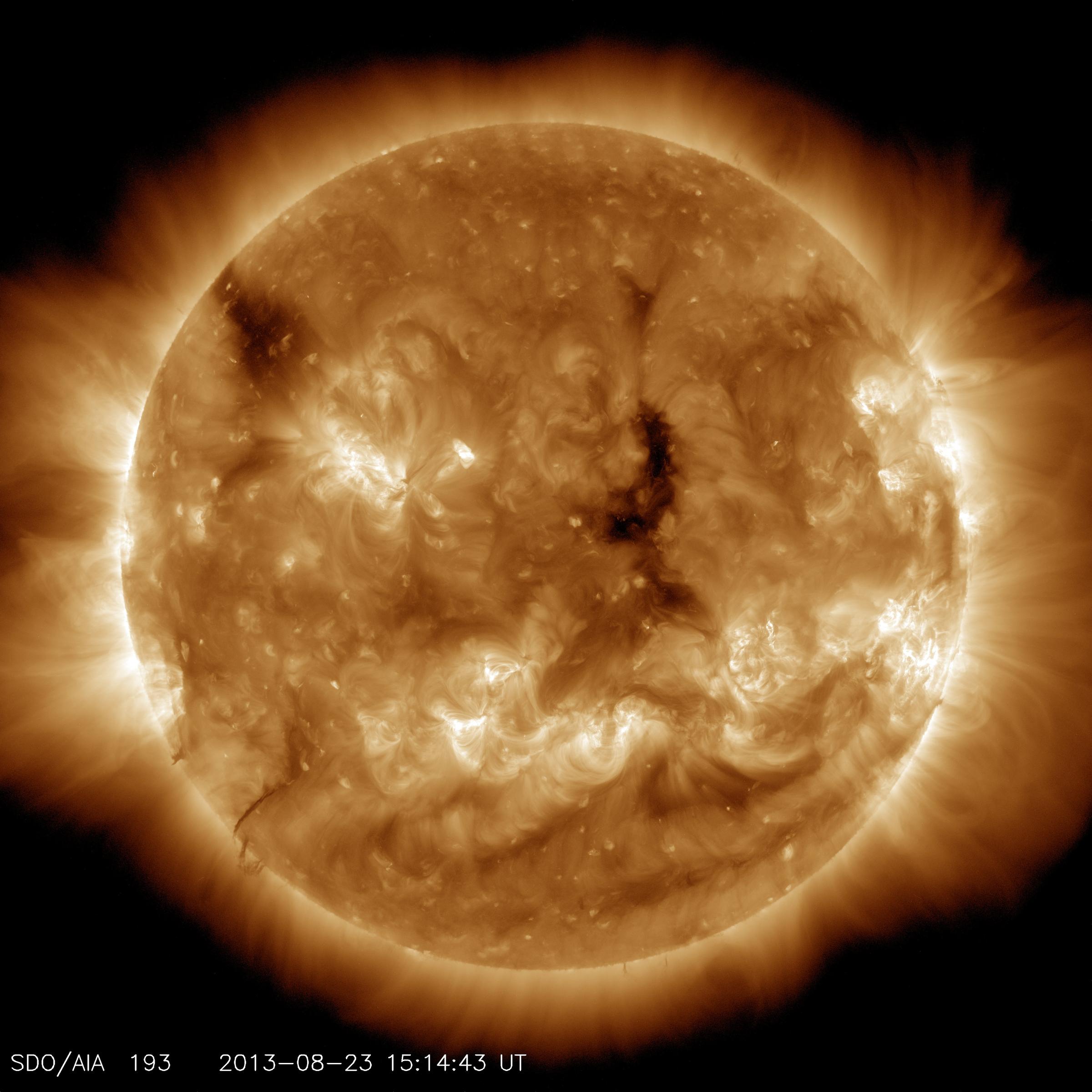

To ensure that all coronavirus particles are killed, it may be. "So, if you think about the amount of particles that actually are striking the heat shield and depositing that heat in, the whole thing gets heated up to 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit. For example, the coronavirus may need to be exposed to temperatures of between 50 and 55C (122 to 131F) for 20 minutes to be killed. The chromosphere is no longer white light like the. "The corona is very tenuous plasma it is not a hugely dense area," Fox said. The temperature in the corona is more than a million degrees, surprisingly much hotter than the temperature at the Suns surface which is around 5,500 C. The temperature increases as you move higher to about 20,000 degrees Celsius at the top of the chromosphere. The individual hydrogen nuclei must collide with enough energy to give a reasonable probability.

That means, over a set amount of time, the heat shield won't hit all that many superhot particles of the plasma that makes up the corona - which means that although each individual collision transfers a fair amount of heat to the shield's surface, the overall increase in the shield's temperature will be tolerable. These reactions are highly sensitive to temperature and density. The photosphere, or visible surface of the Sun, typically measures up to 10,000 F (5,540 C). The more bearable temperature is thanks to the thin, wispy structure of the corona itself, which is the atmosphere that can't be seen without blocking out the photosphere - the incredibly bright layer that we think of as the surface of the sun. Coronal gases reach temperatures of 1,800,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,000,000 C) or more. A NASA probe has become the first spacecraft to touch the sun, traveling into a region where the temperature is a spicy 2 million degrees-Fahrenheit. "Think of putting your oven on and you set it at 400 degrees, and you can put your hand inside your oven and you won't get burned unless you actually touch a surface," Parker Solar Probe project scientist Nicola Fox, a solar scientist at Johns Hopkins University, said on July 20 during a NASA news conference about the upcoming mission.

But even the hot side of the heat shield won't actually hit millions of degrees itself, despite flying through the hottest part of the sun.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)